Aftermath

Praised in West, scorned at home

"Because of him, we have economic confusion!"

"Because of him, we have opportunity!"

"Because of him, we have political instability!"

"Because of him, we have freedom!"

"Complete chaos!"

"Hope!"

"Political instability!"

"Because of him, we have many things like Pizza Hut!"

Thus ran the script to the 1997 advert that saw a tableful of men argue loudly over the outcome of Perestroika in

a newly-opened Moscow restaurant, a few meters from an awkward Gorbachev, staring into space as he munches his

food alongside his 10 year-old granddaughter. The TV spot ends with the entire clientele of the restaurant getting

up to their feet, and chanting "Hail to Gorbachev!" while toasting the former leader with pizza slices

heaving with radiant, viscous cheese.

The whole scene is a travesty of the momentous transformations played out less than a decade earlier, made

crueler by contemporary surveys among Russians that rated Gorbachev as the least popular leader in the country's

history, below Stalin and Ivan the Terrible.

The moment remains the perfect encapsulation of Gorbachev's post-resignation career.

To his critics, many Russians among them, he was one of the most powerful men in the world reduced to exploiting

his family in order to hawk crust-free pizzas for a chain restaurant — an American one at that — a

personal and national humiliation, and a reminder of his treason. For the former Communist leader himself it was

nothing of the sort. A good-humored Gorbachev said the half-afternoon shoot was simply a treat for his family, and

the self-described "eye-watering" financial reward — donated entirely to his foundation —

money that would be used to go to charity.

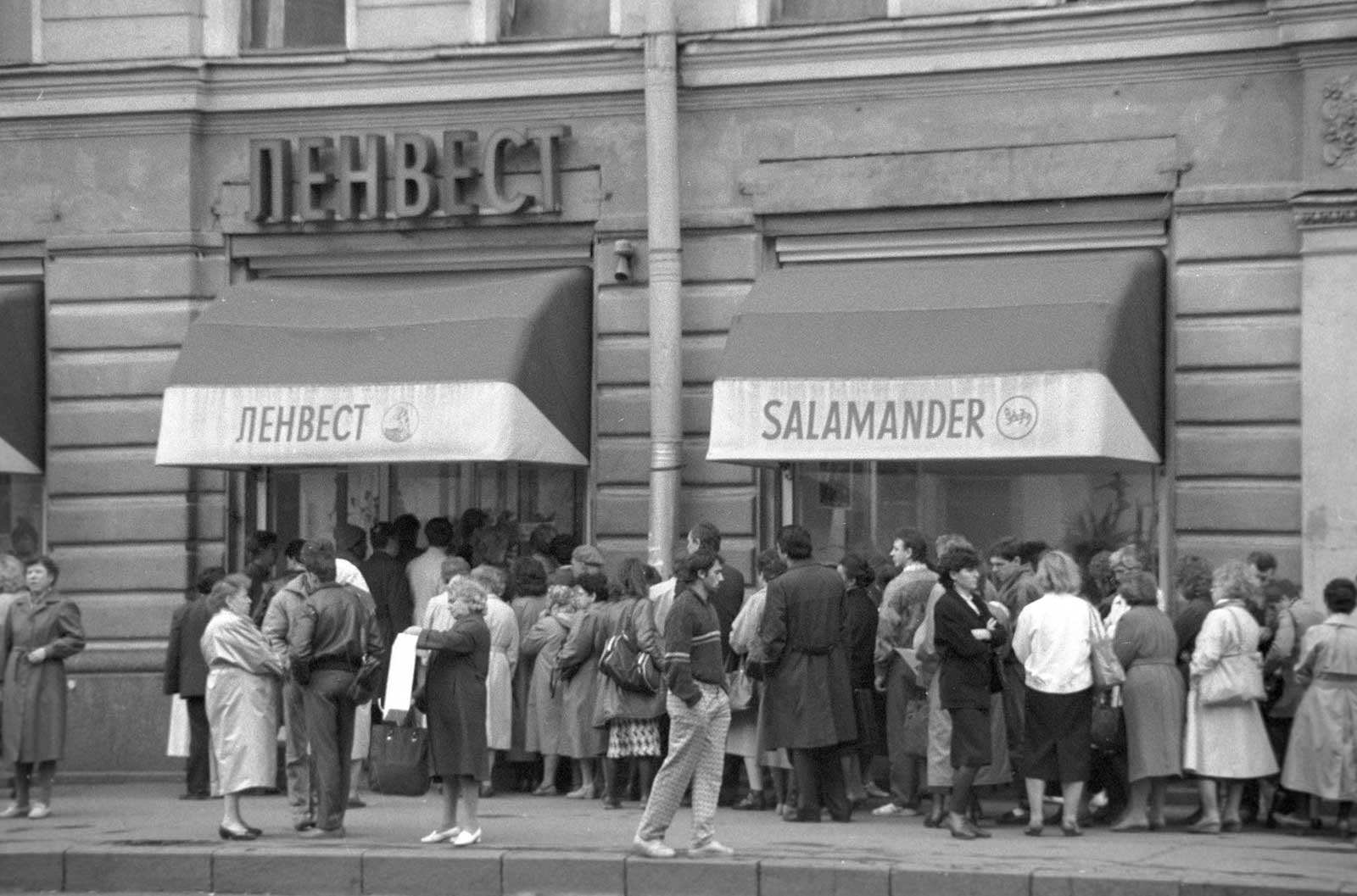

As for the impact of Gorbachev's career in advertising on Russia's reputation… In a country where a decade before

the very existence of a Pizza Hut near Red Square seemed unimaginable, so much had changed, it seemed a perversely

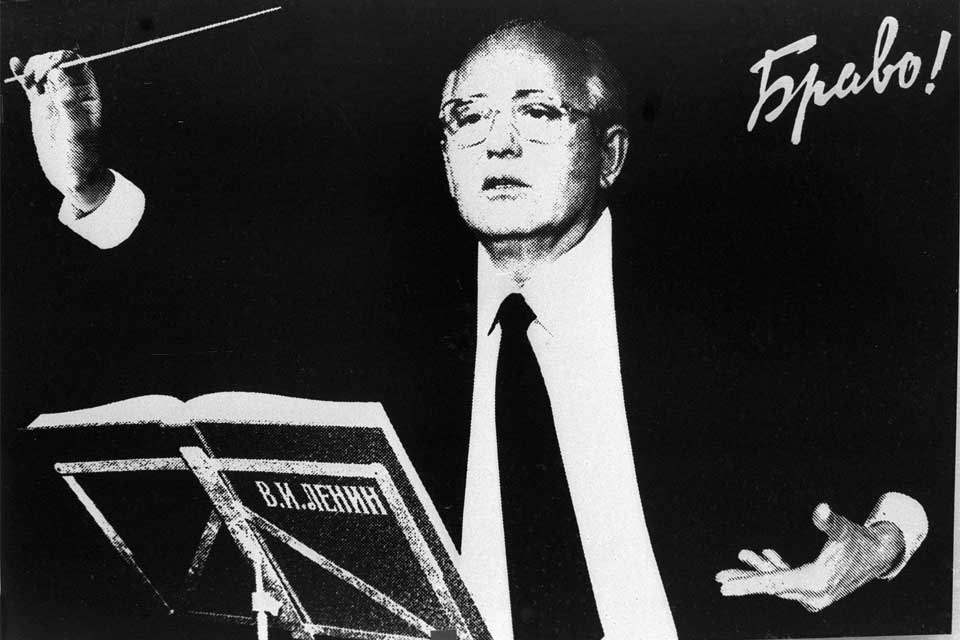

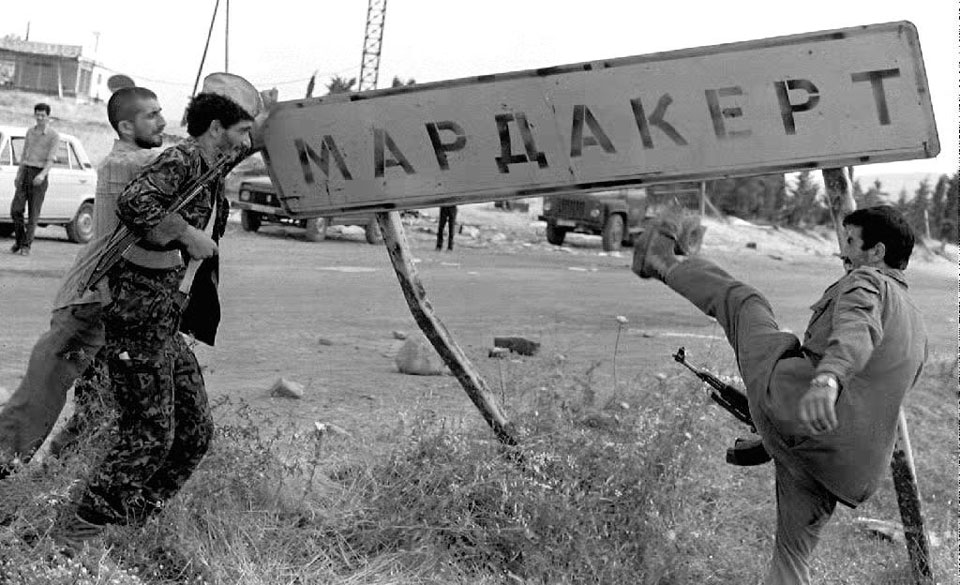

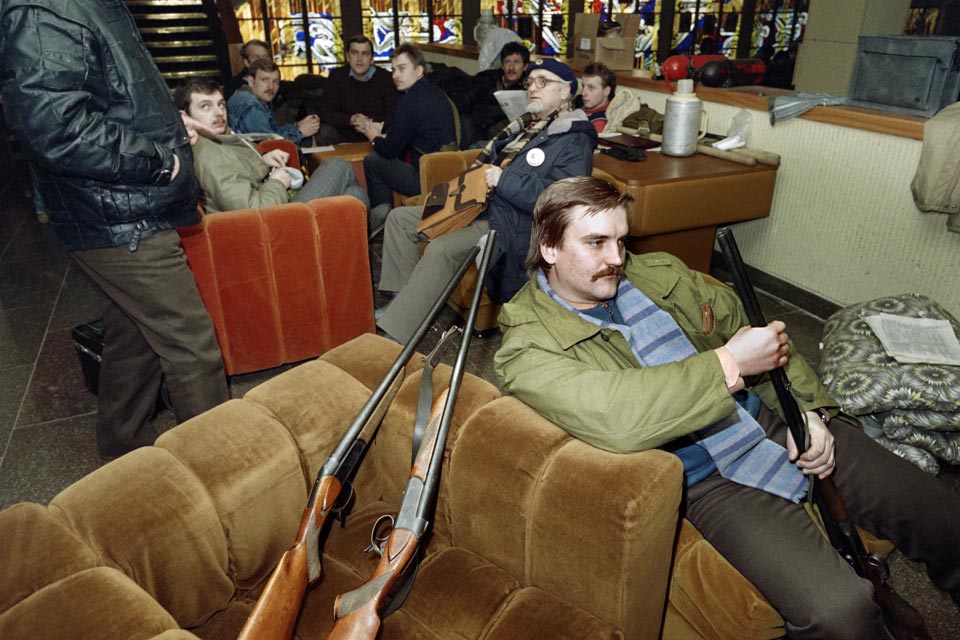

logical, if not dignified, way to complete the circle. In the years after Gorbachev's forced retirement there had

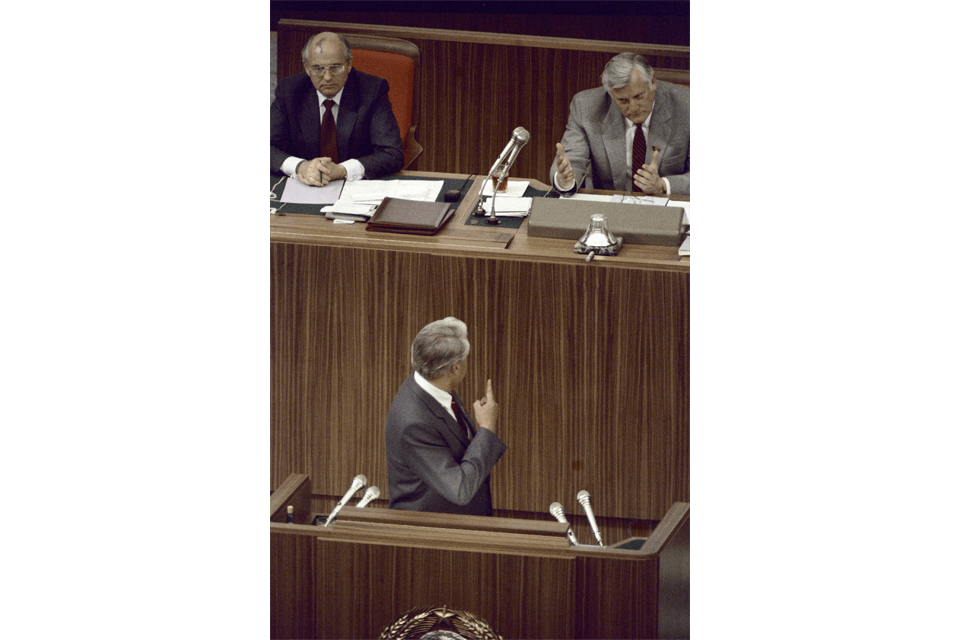

been an attempted government overthrow that ended with the bombardment of parliament, privatization, the first

Chechen War, a drunk Yeltsin conducting a German orchestra and snatching an improbable victory from revanchist

Communists two years later, and an impending default.

Although he did get 0.5 percent of the popular vote during an aborted political comeback that climaxed in the

1996 presidential election, Gorbachev had nothing at all to do with these life-changing events. And unlike Nikita

Khrushchev, who suffered greater disgrace, only to have his torch picked up, Gorbachev's circumstances were too

specific to breed a political legacy. More than that, his reputation as a bucolic bumbler and flibbertigibbet,

which began to take seed during his final years in power, now almost entirely overshadowed his proven skill as a

political operator, other than for those who bitterly resented the events he helped set in motion.

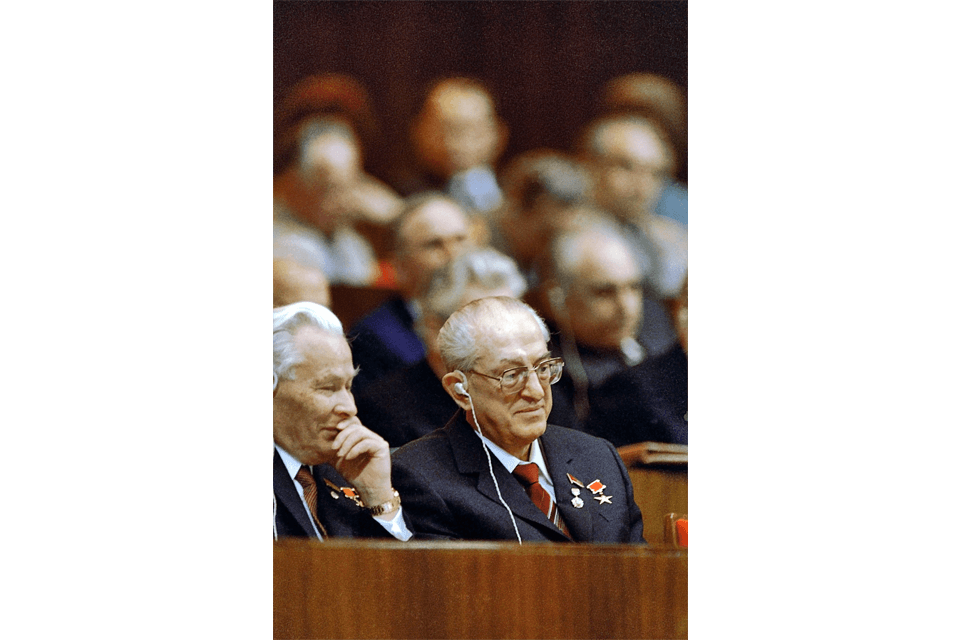

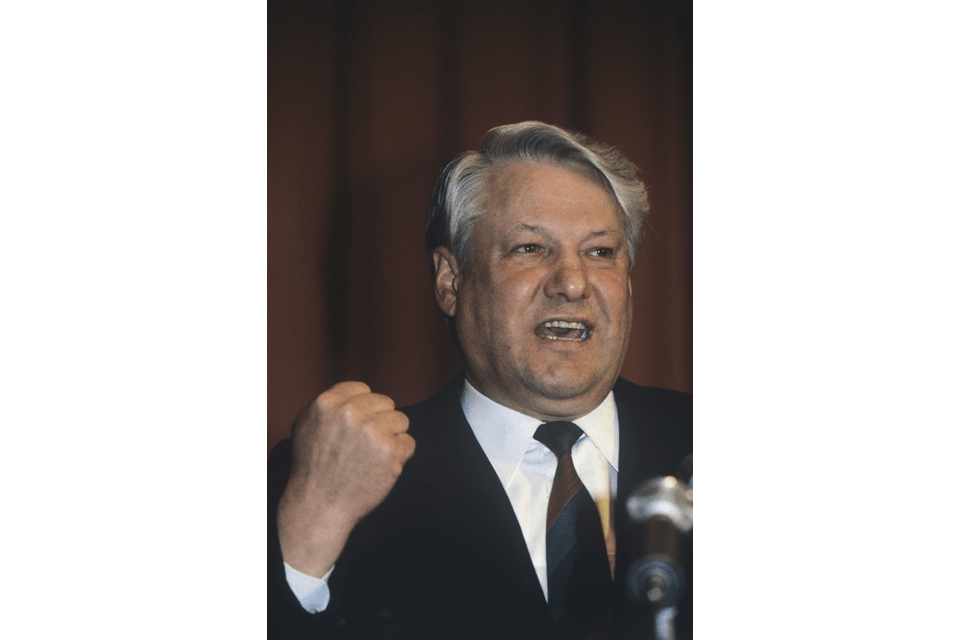

Other than in his visceral dislike of Boris Yeltsin — the two men never spoke after December 1991 —

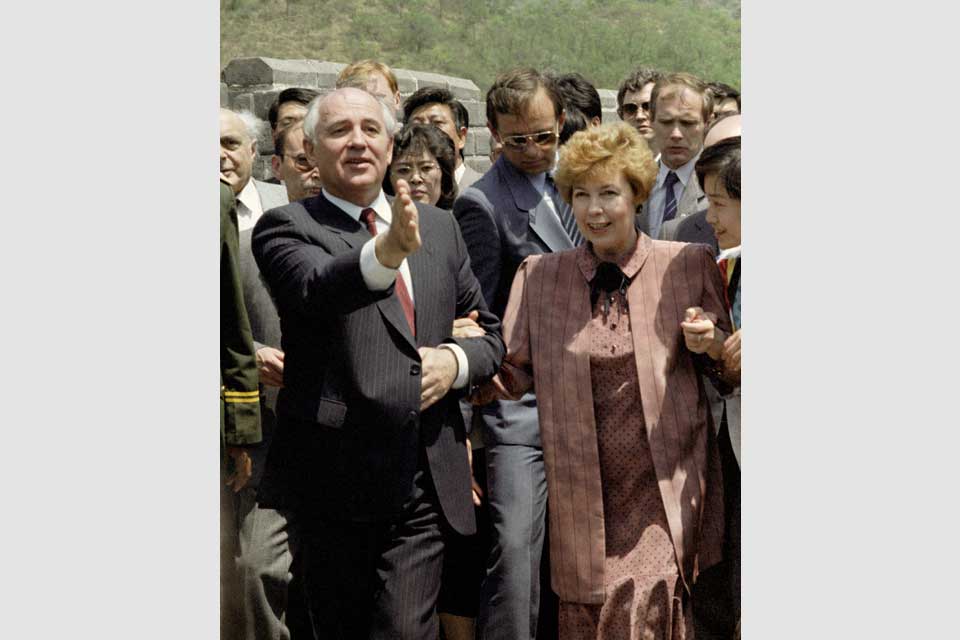

if Gorbachev was bitter about the lack of respect afforded to him at home, he wore it lightly. Abroad, he reveled

in his statesmanlike aura, receiving numerous awards, and being the centerpiece at star-studded galas. Yet, for a

man of his ambition, being pushed into retirement must have gnawed at him repeatedly.

After eventually finding a degree of financial and personal stability on the lecture circuit in the late 1990s,

Gorbachev was struck with another blow — the rapid death of Raisa from cancer.

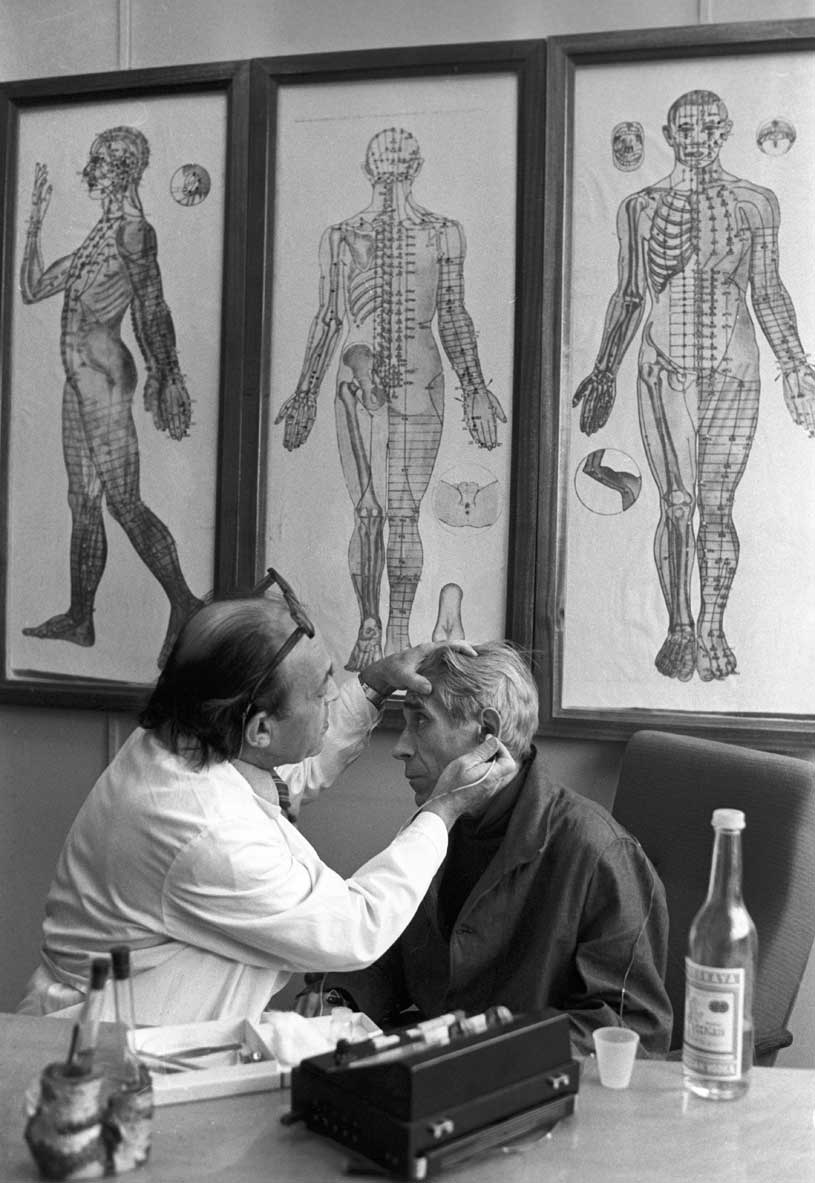

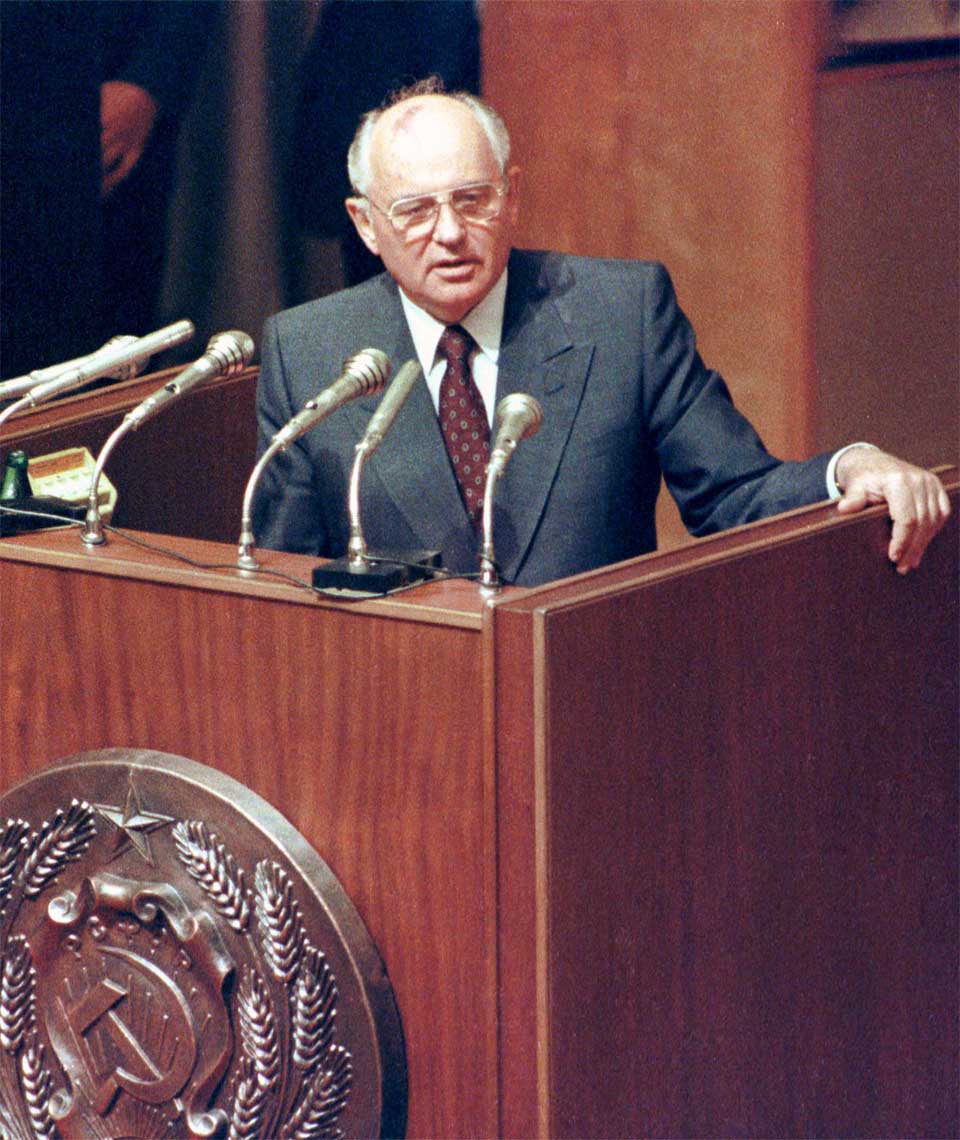

A diabetic, Gorbachev became immobile and heavy-set, a pallor fading even his famous birthmark. But his voice

retained its vigor (and accent) and the former leader continued to proffer freely his loquacious opinions on

politics, to widespread indifference.

Gorbachev's legacy is at the same time unambiguous, and deeply mixed — more so than the vast majority of

political figures. His decisions and private conversations were meticulously recorded and verified. His

motivations always appeared transparent. His mistakes and achievements formed patterns that repeated themselves

through decades.

Yet for all that clarity, the impact of his decisions, the weight given to his feats and failures can be debated

endlessly, and has become a fundamental question for Russians.

Less than three decades after his limo left the Kremlin, his history has been rewritten several times, and his

role bent to the needs of politicians and prevailing social mores. This will likely continue. Those who believe in

the power of the state, both nationalists and Communists, will continue to view his time as egregious at best,

seditious at worst. For them, Gorbachev is inextricably linked with loss — the forfeiture of Moscow's

international standing, territory and influence. The destruction of the fearsome and unique Soviet machine that

set Russia on a halting course as a middle-income country with a residual seat in the UN Security Council trying

to gain acceptance in a US-molded world.

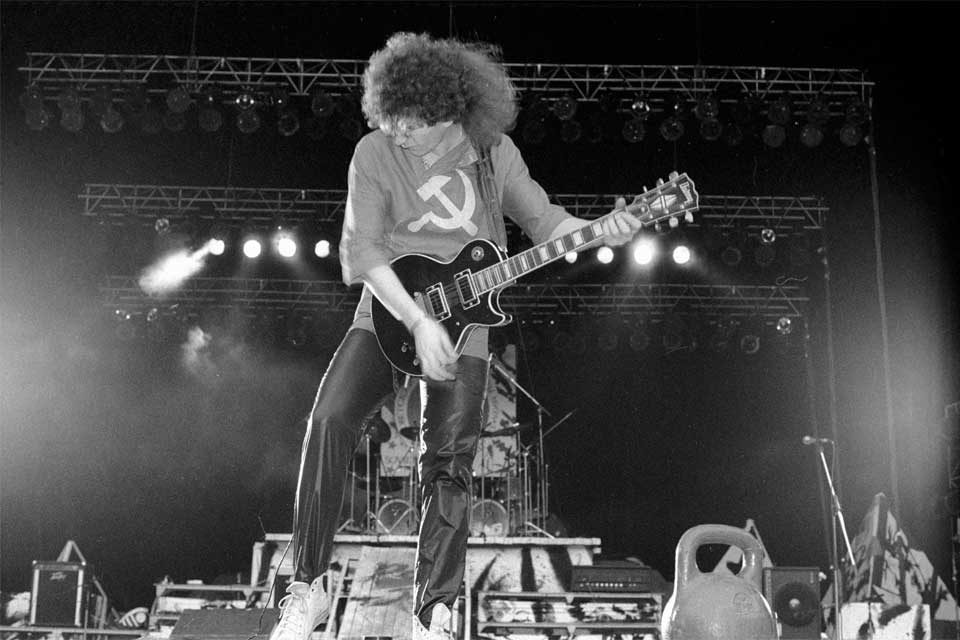

Others, who appreciate a commitment to pacifism and democracy, idealism and equality, will also find much to

admire in Gorbachev, even though he could not always be his best self. Those who place greater value on the

individual than the state, on freedom than on military might, those who believe that the collapse of the Iron

Curtain and the totalitarian Soviet Union was a landmark achievement not a failure will be grateful, and if not

sympathetic. For one man's failure can produce a better outcome than another's success.